The culinary world reveres Japanese knives for their exceptional sharpness and precision. A critical factor contributing to this renowned performance is the specific japanese knives angle, which is meticulously designed and maintained. Understanding the nuances of these angles is paramount for any chef or enthusiast looking to unlock the full potential of their blades.

This comprehensive guide delves deep into every facet of japanese knives angle, from their historical roots to advanced maintenance techniques. We will explore why these angles differ significantly from Western counterparts and how they are optimized for diverse culinary tasks.

Unveiling the Precision: The World of Japanese Knife Angles

Beyond Sharpness: Why Angle Matters for Japanese Knives

Sharpness is often the first characteristic people associate with Japanese knives. However, true performance extends far beyond mere keenness. The specific japanese knives angle dictates not only how sharp an edge can be, but also its durability, its ability to glide through different food types, and its overall longevity.

A finely tuned angle minimizes resistance, making slicing and dicing an effortless experience. This precision is essential for delicate tasks like preparing sushi or thinly slicing vegetables for garnishes. The angle influences the geometry of the blade and its interaction with the ingredients.

Incorrect angles can lead to a multitude of problems, including premature dulling, chipping, or rolling of the edge. Therefore, mastering the art of maintaining the proper japanese knives angle is as crucial as selecting the right knife itself.

A Legacy of Edge Geometry: Understanding the Japanese Approach

The approach to edge geometry in Japan is rooted in centuries of sword-making tradition. This heritage has profoundly influenced the design and sharpening philosophy of kitchen knives. Unlike Western knives, which often prioritize robust, symmetrical edges for heavy-duty tasks, Japanese knives are frequently designed for specific, precise cuts.

This specialization leads to a wide array of blade profiles and, consequently, unique sharpening angles. From the delicate single-bevel yanagiba to the versatile double-bevel gyuto, each blade’s angle is a reflection of its intended purpose and the cultural context of Japanese cuisine.

The pursuit of an exquisite edge is a form of art in Japan, where blacksmiths and sharpeners spend decades perfecting their craft. This dedication ensures that every Japanese knife is not just a tool, but a masterpiece of functional design, with its angle being a central component of its identity and performance.

The Foundational Philosophy of Japanese Knife Angles

Eastern vs. Western: A Comparative Look at Blade Geometry

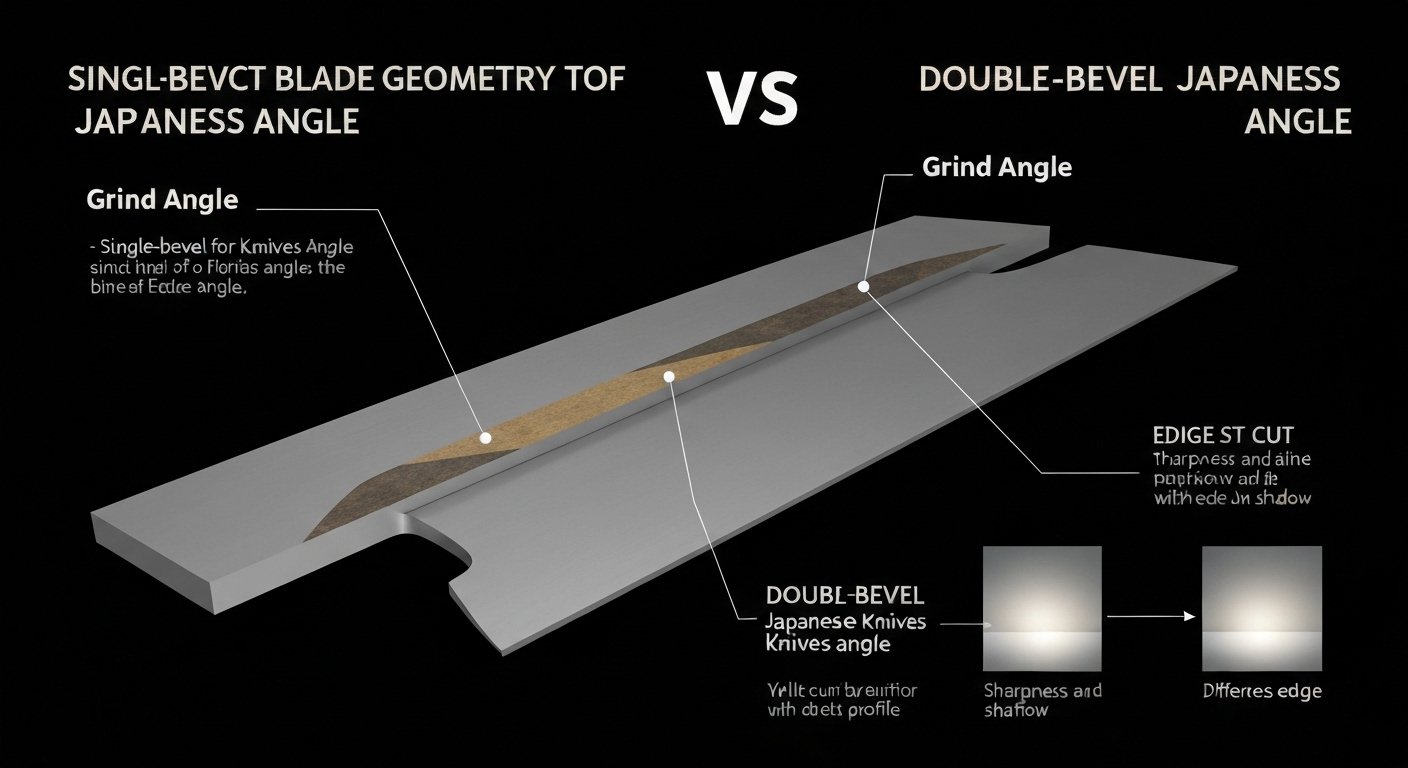

The most significant distinction when discussing blade geometry lies in the fundamental design philosophy between Eastern and Western knives. Western knives, typically from European traditions, often feature a double-bevel edge, ground symmetrically on both sides of the blade. These angles are generally wider, ranging from 20 to 25 degrees per side, resulting in an overall edge angle of 40-50 degrees.

This robust angle makes Western knives durable and versatile, suitable for a wide range of chopping and heavy-duty tasks. Brands like Wüsthof and Zwilling J.A. Henckels exemplify this approach, designing blades that can withstand significant impact and lateral force during use. The thickness behind the edge is also often greater, contributing to their resilience.

In contrast, Japanese knives often exhibit much finer angles, sometimes as low as 10-15 degrees per side for double-bevel blades, leading to an overall edge of 20-30 degrees. Moreover, many traditional Japanese knives are single-bevel, meaning they are sharpened on only one side, with the opposite side being flat or slightly concave. This asymmetric grind creates an incredibly acute angle, allowing for unparalleled sharpness and precision.

The single-bevel design, common in knives like the Deba or Yanagiba, results in an edge that can be as fine as 7-10 degrees on the sharpened side. This extreme thinness behind the edge, combined with the acute angle, enables surgical precision and minimal resistance when cutting through ingredients. The differing philosophies reflect the distinct culinary traditions and priorities of each culture.

Understanding these fundamental differences is crucial before delving into the specifics of japanese knives angle maintenance. It highlights that what might be considered “sharp” for a Western knife is often just the starting point for a Japanese blade’s capabilities.

The Historical Evolution of Japanese Knife Angles

The evolution of japanese knives angle is inextricably linked to the history of sword-making in feudal Japan. The samurai sword, or katana, was not merely a weapon but a testament to sophisticated metallurgy and meticulous craftsmanship. The techniques developed for creating these legendary blades, particularly in forging and differential hardening, laid the groundwork for kitchen knife production.

Early Japanese kitchen knives, particularly those used by chefs in the imperial court or for ceremonial purposes, borrowed heavily from sword-making traditions. The development of single-bevel blades, for instance, can be traced back to their effectiveness in cutting specific ingredients with unparalleled precision, a characteristic highly valued in traditional Japanese cuisine.

Over centuries, different regions in Japan developed their own distinct knife-making styles and preferred angles, adapting to local culinary needs and available materials. For example, Sakai, a city near Osaka, became famous for its single-bevel knives (Honyaki and Kasumi styles), while Seki, in Gifu Prefecture, became a hub for mass-produced knives and, later, a blend of traditional and modern knife-making techniques.

The Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century brought significant changes, including the influx of Western technologies and culinary influences. This led to the development of double-bevel Japanese knives, such as the Gyuto (chef’s knife) and Santoku, which blended traditional Japanese craftsmanship with Western versatility. These knives often adopted a slightly wider angle than their single-bevel counterparts but still maintained a finer edge than typical Western knives.

Today, the tradition continues with master blacksmiths dedicating their lives to preserving and innovating these historical techniques. The history teaches us that the japanese knives angle is not arbitrary but a product of generations of refinement, driven by a deep understanding of metallurgy, geometry, and culinary art.

How Steel Properties Influence Ideal Japanese Knife Angles

The type of steel used in a Japanese knife significantly dictates its ideal sharpening angle. Japanese knives are renowned for their use of high-carbon steels, often with very high hardness ratings on the Rockwell scale (HRC 60-67). This high hardness allows for the creation and retention of extremely acute angles.

Carbon steels like Aogami (Blue Steel) and Shirogami (White Steel), produced by Hitachi Metals, are prized for their ability to take an exceptionally fine edge. Their fine grain structure and minimal impurities mean they can be sharpened to very acute angles (e.g., 10-15 degrees per side for double bevel, or 7-10 degrees for single bevel) without chipping or rolling, and they hold that edge for an extended period.

Conversely, softer stainless steels, while more corrosion-resistant, might not hold such acute angles as effectively. If a softer steel is sharpened to too fine an angle, the edge is more prone to rolling or deforming under stress. Therefore, knives made from steels like VG-10 or AUS-8, while still capable of excellent sharpness, might perform better with a slightly less acute japanese knives angle, perhaps 15 degrees per side, to ensure better durability.

Super steels or powder metallurgy steels, such as SG2 (R2) or ZDP-189, represent the pinnacle of modern steel technology. These steels combine extreme hardness with impressive toughness and corrosion resistance. They can maintain incredibly fine edges, often pushing the boundaries of what is possible with traditional carbon steels, allowing for very aggressive and precise angles.

Understanding the interplay between steel properties and blade geometry is paramount for proper sharpening. A sharpener must consider the steel’s hardness, toughness, and wear resistance to determine the optimal japanese knives angle for maximum performance and edge longevity. Sharpening a high-HRC carbon steel knife to a very acute angle is possible precisely because of its inherent properties.

Decoding the Bevel: Single vs. Double Edge Japanese Knives Angle

The Uniqueness of Single-Bevel Japanese Knives: Specialized Angles

Single-bevel Japanese knives represent a unique and traditional aspect of Japanese cutlery, designed for highly specialized tasks. Unlike their Western counterparts, these knives are sharpened predominantly on one side, creating an extremely acute and precise cutting edge. The opposite side, known as the ‘ura’ or concave side, is typically flat or slightly hollow-ground, which helps to reduce drag and prevent food from sticking to the blade.

The primary edge angle on a single-bevel knife can be incredibly fine, often ranging from 7 to 10 degrees. This acute japanese knives angle allows the blade to slice through ingredients with minimal resistance, producing incredibly clean and precise cuts. For instance, a Yanagiba, used for slicing fish for sashimi, utilizes its single bevel to make long, uninterrupted, smooth cuts that preserve the delicate texture of the fish.

Similarly, the Deba, a robust single-bevel knife for filleting fish and breaking down poultry, has a stronger, yet still acute, angle designed to withstand tougher tasks while maintaining excellent cutting performance. The unique geometry of a single-bevel knife also means that it naturally steers the cut, which can be advantageous for specific culinary techniques, such as creating paper-thin slices.

Sharpening a single-bevel knife requires a different technique compared to a double-bevel knife. The sharpener must maintain the primary bevel angle meticulously while also addressing the ura side to remove any burr and ensure proper food release. This process is more intricate and requires a deep understanding of the knife’s geometry and its intended use. The precision of these angles is what makes single-bevel knives indispensable for traditional Japanese cuisine.

Mastering Double-Bevel Japanese Knife Angles: Versatility and Precision

While single-bevel knives are specialized, double-bevel Japanese knives offer a balance of versatility and precision that appeals to a broader range of users, from professional chefs to home cooks. These knives, like the Gyuto (chef’s knife) or Santoku, are sharpened on both sides of the blade, similar to Western knives, but typically at much finer angles.

The common japanese knives angle for double-bevel blades usually falls within the range of 10-15 degrees per side, resulting in an overall edge angle of 20-30 degrees. This is significantly more acute than the 20-25 degrees per side (40-50 degrees total) often seen in Western knives. This finer angle allows for superior sharpness and a cleaner cut, reducing cell damage in ingredients and preserving their freshness and flavor.

The versatility of double-bevel Japanese knives stems from their ability to perform a wide array of tasks, from slicing and dicing vegetables to processing meats. The symmetrical grind allows for ambidextrous use, making them accessible to a wider audience. Brands like Shun and Global have popularized these types of knives globally, offering excellent performance due to their optimized angles.

Maintaining these angles involves sharpening both sides evenly to achieve a truly symmetrical and keen edge. While perhaps less daunting than sharpening a single-bevel knife, it still requires precision and practice to ensure consistent angles along the entire length of the blade. The goal is to achieve an edge that is both incredibly sharp and resilient enough for daily use in a busy kitchen environment.

The popularity of double-bevel Japanese knives highlights a successful fusion of traditional Japanese craftsmanship with the practical demands of modern cooking. Their optimized japanese knives angle is central to their reputation for exceptional cutting performance and user-friendliness.

Asymmetrical Grinds: A Deep Dive into Common Japanese Knives Angle Variations

Beyond the fundamental distinction between single and double-bevel knives, many Japanese blades feature asymmetrical grinds, even within the category of double-bevel knives. This nuanced approach to blade geometry significantly impacts the cutting performance and intended use of the knife. An asymmetrical grind means that while both sides are sharpened, one side (typically the right side for right-handed users) has a more acute angle or a more pronounced primary bevel than the other.

This subtle asymmetry is often seen in general-purpose knives like the Gyuto or Santoku, where the right side might be ground at, for example, 10 degrees, and the left side at 12-15 degrees. This creates a slightly off-center edge, which enhances the knife’s ability to “steer” through ingredients, especially when pushing cuts. It also helps to reduce stickage, similar to the function of the ura on a single-bevel blade, by creating a small air pocket behind the cut.

Examples of specific asymmetrical grinds include the ‘kiritsuke tip’ often found on Gyuto knives, which combines elements of the traditional Yanagiba and Usuba. This tip profile allows for precise piercing and delicate work. Another variation is the ‘hollow grind’ or ‘granton edge’ (though more common in Western knives, some Japanese designs incorporate similar principles) where scallops are ground into the blade face to reduce surface area and minimize friction.

Understanding these variations in japanese knives angle and grind is crucial for effective sharpening. When sharpening an asymmetrical double-bevel knife, it’s important to recognize that you are not aiming for perfectly symmetrical angles on both sides. Instead, the goal is to reproduce the manufacturer’s intended asymmetry, maintaining the distinct angles on each side to preserve the knife’s unique cutting characteristics.

This sophisticated approach to grind geometry is a hallmark of Japanese knife making, reflecting a deep understanding of how subtle differences in the blade’s profile can profoundly affect its functionality and the user’s experience. It’s another layer of precision that distinguishes Japanese cutlery.

Factors Dictating the Optimal Japanese Knife Angle

Intended Use: Tailoring Angles for Specific Culinary Tasks

The primary determinant of the optimal japanese knives angle is the knife’s intended use. Japanese cuisine is highly specialized, and so are its tools. A knife designed for slicing delicate fish requires a vastly different edge geometry than one meant for butchering poultry or finely dicing vegetables.

For ultra-fine slicing tasks, such as preparing sashimi with a Yanagiba or filleting fish with a Sujihiki, the most acute angles are preferred. These knives typically feature a single-bevel design or a very pronounced asymmetrical double-bevel, allowing for minimal resistance and exceptionally clean cuts that preserve the delicate texture of the food. An angle of 7-10 degrees on the cutting side is common for these specialized blades, enabling them to glide through ingredients with surgical precision.

Conversely, knives designed for more robust tasks, like breaking down fish bones with a Deba or chopping hard vegetables with a Nakiri, require a more durable edge. While still acute by Western standards, their angles might be slightly wider to prevent chipping, perhaps 12-15 degrees per side for a double-bevel Nakiri, or a slightly sturdier angle for a single-bevel Deba. The emphasis here is on stability and resilience without sacrificing much sharpness.

General-purpose knives like the Gyuto or Santoku strike a balance, offering versatility for a wide range of kitchen tasks. Their typical japanese knives angle of 10-15 degrees per side (20-30 degrees overall) provides an excellent combination of sharpness and durability suitable for daily use. This balance allows them to perform well in various cutting motions, from push cuts to rock chops.

Ultimately, the optimal angle is always a compromise between ultimate sharpness and edge durability. A professional sharpener will consider the specific tasks the knife will undertake and adjust the angle accordingly, ensuring the knife performs optimally for its designated purpose. This tailored approach is a cornerstone of Japanese knife philosophy, where each tool is a specialist.

Steel Hardness and Edge Retention: Angle Implications for Different Alloys

The hardness of the steel plays a crucial role in determining the ideal japanese knives angle and its edge retention capabilities. High-carbon steels, common in traditional Japanese knives (e.g., White Steel, Blue Steel), are known for their exceptional hardness, often reaching 60-67 HRC. This extreme hardness allows these steels to be sharpened to very acute angles without suffering from immediate deformation or rolling of the edge. The fine grain structure of these steels enables them to hold such a delicate edge for extended periods, delivering superior cutting performance.

However, while hard steels can take and hold a very fine edge, they can also be more brittle. Sharpening them to an excessively acute angle for tasks involving lateral stress or impacts might lead to micro-chipping. Therefore, even with very hard steels, the chosen angle needs to balance maximum sharpness with sufficient toughness for the intended application.

Modern stainless steels like VG-10, AUS-8, and SG2 (R2 powder steel) are also widely used in Japanese knives. VG-10 and AUS-8, while generally softer than traditional carbon steels (typically 58-61 HRC), still offer a good balance of sharpness, durability, and corrosion resistance. They can be sharpened to respectable angles, but might benefit from slightly less acute angles (e.g., 15 degrees per side) compared to their harder carbon steel counterparts to ensure optimal edge stability.

SG2 (R2) powder steel, on the other hand, is a super steel that combines very high hardness (62-64 HRC) with excellent toughness and wear resistance. This allows knives made from SG2 to take and hold extremely acute edges, rivalling or even surpassing traditional carbon steels, while offering better corrosion resistance. For these premium steels, very fine japanese knives angle can be maintained with confidence.

In essence, a sharper angle generally means better cutting performance, but it also means a more delicate edge. The hardness and toughness of the steel determine how delicate that edge can be before it becomes prone to damage. Experienced sharpeners understand these material properties and adjust their angles accordingly to maximize both cutting ability and edge longevity.

Blade Profile and Geometry: How Design Influences the Sharpening Angle

The overall blade profile and geometry significantly influence the optimal japanese knives angle and how the knife performs. Beyond the edge angle itself, factors like blade thickness, distal taper, and the presence of a ‘shinogi’ (the line defining the primary bevel) all play a critical role in the knife’s cutting efficiency and its interaction with food.

A thin blade, particularly behind the edge, will naturally cut with less resistance, even if the primary edge angle is not extremely acute. Many Japanese knives are characterized by their very thin grind from the spine to the edge (distal taper), which facilitates easy slicing. This thinness allows for a sharper feel even at slightly wider angles, as there is less material to wedge apart the food.

For single-bevel knives, the ‘shinogi’ line is crucial. It defines the primary bevel’s angle and how steep the knife’s grind is. Maintaining this line during sharpening is paramount to preserve the knife’s intended cutting performance and prevent damage to the blade’s face. The ‘ura’ or concave back, by creating an air pocket, further reduces drag, allowing the ultra-acute single-bevel edge to perform optimally.

The type of grind also matters. A convex grind, where the blade curves slightly outward from the spine to the edge, offers both strength and good cutting performance by reducing friction. A flat grind, common in many double-bevel knives, creates a clean, straight edge that is relatively easy to sharpen. Each grind style requires a slightly different approach to sharpening to maintain its inherent benefits and intended angle.

Even the tip’s geometry, whether a pointed kiritsuke tip or a more rounded gyuto tip, influences how the knife interacts with food and how specific cutting techniques are performed. All these elements of blade design contribute to the knife’s overall cutting feel and dictate the precise japanese knives angle that will maximize its potential, making it a cohesive system where every part supports the whole.

Precision Tools and Techniques for Maintaining the Correct Japanese Knives Angle

Whetstones and Freehand Sharpening: Cultivating the Feel for the Angle

The traditional and most revered method for maintaining the correct japanese knives angle is freehand sharpening on whetstones. This technique, though requiring practice and patience, offers unparalleled control and allows the sharpener to truly understand the blade’s geometry and how it interacts with the stone.

Whetstones, or water stones, come in various grits, from coarse (120-400 grit) for repairing damaged edges and establishing new angles, to medium (800-2000 grit) for general sharpening and refining, and fine (3000-8000+ grit) for polishing the edge to a mirror finish. The progressive use of grits ensures that the edge is not only incredibly sharp but also durable.

The core of freehand sharpening lies in maintaining a consistent angle throughout the sharpening process. This is achieved by feeling the bevel flat against the stone and using a stable grip. Many experienced sharpeners describe it as “feeling for the burr” – a tiny wire edge that forms on the opposite side of the blade when the metal has been sufficiently removed from one side. This burr indicates that the edge has been fully thinned out to its apex.

For double-bevel knives, the process involves sharpening one side until a burr forms, then flipping the knife and sharpening the other side until the burr transfers. For single-bevel knives, the primary bevel is sharpened extensively, then the ura (back side) is gently flattened on a very fine stone to remove the burr and polish the concave surface. Cultivating the “feel” for the angle comes with hours of practice, developing muscle memory and an intuitive understanding of the blade’s relationship with the stone. There are numerous tutorials available online, such as those from reputable sources like JKI (Japanese Knife Imports) or Burrfection, which can guide beginners.

This method not only sharpens the knife but also helps in understanding the subtle nuances of each blade’s unique japanese knives angle and how it performs. It is a meditative and rewarding process that connects the user deeply with their tools, fostering a profound appreciation for their sharpness and precision.

Angle Guides and Sharpening Systems: Aiding Consistency

While freehand sharpening on whetstones is the traditional ideal, it has a steep learning curve. For those new to sharpening or seeking greater consistency, angle guides and sharpening systems offer excellent alternatives or supplements for maintaining the precise japanese knives angle.

Simple angle guides are small clips or wedges that attach to the spine of the knife, designed to set a specific angle (e.g., 15 or 20 degrees) relative to the whetstone. These guides eliminate much of the guesswork, allowing users to focus on the motion of sharpening rather than constantly adjusting their wrist angle. They are particularly useful for maintaining consistent angles on double-bevel knives and can be a great stepping stone before attempting full freehand sharpening. Brands like King and Naniwa offer simple clip-on guides.

More elaborate sharpening systems, such as the Wicked Edge, KME Sharpeners, or Edge Pro Apex, provide a jig-based approach. These systems securely clamp the knife in place and use guided rods with abrasive stones to maintain incredibly precise and repeatable angles on both sides of the blade. They allow for micro-adjustments in angle, down to fractions of a degree, making them ideal for achieving consistent and razor-sharp edges on even the most delicate Japanese knives.

While these systems can be a significant investment, they offer unparalleled accuracy and consistency, making them valuable tools for enthusiasts and professionals who need to maintain a large collection of knives. They minimize the risk of inconsistent angles, which can lead to dull spots or uneven wear on the edge. Using these systems can effectively bridge the gap between a novice sharpener and the precision typically achieved by master freehand sharpeners, ensuring that the critical japanese knives angle is always perfectly maintained.

Advanced Angle Measurement: Digital and Analog Solutions for Japanese Knives

For those seeking absolute precision in maintaining the japanese knives angle, various advanced measurement tools are available. These tools allow sharpeners to quantify their angles accurately, providing immediate feedback and aiding in the replication of specific edge geometries.

Analog angle indicators, often simple protractors or angle cubes, can be placed directly on the blade’s bevel while it rests on the stone. These provide a quick visual approximation of the angle. While not as precise as digital tools, they are inexpensive and useful for basic consistency checks, especially for beginners learning to establish a feel for common angles like 15 or 20 degrees.

Digital angle gauges are far more precise and have become indispensable for serious sharpeners. These compact devices typically feature a magnetic base that adheres to the blade or the sharpening system, and they provide a digital readout of the angle relative to the surface they are placed on. By placing the gauge on the stone and then on the knife’s bevel, one can accurately determine the exact sharpening angle. Some advanced models can even measure the angle of the blade in relation to the vertical plane, providing a true edge angle measurement.

Furthermore, specialized tools exist for measuring the primary bevel of single-bevel knives or the overall blade geometry. These might include calipers for measuring blade thickness at different points or custom-made jigs that help visualize the complex curves of a hollow grind. Advanced users might even employ microscopic inspection to evaluate the edge’s apex, burr formation, and overall symmetry, ensuring the japanese knives angle is perfectly formed and free of micro-imperfections.

While not strictly necessary for basic sharpening, these advanced measurement tools empower sharpeners to achieve professional-level accuracy and consistency. They are particularly valuable when trying to replicate a specific factory angle, experiment with different angles for various tasks, or troubleshoot sharpening issues. Investing in a quality digital angle gauge can significantly elevate one’s sharpening capabilities and understanding of blade geometry.

The Long-Term Impact of Japanese Knives Angle Maintenance

Edge Longevity and Durability: The Consequences of Incorrect Angles

The correct maintenance of the japanese knives angle is paramount for ensuring not just immediate sharpness but also the long-term longevity and durability of the blade. An improperly sharpened or maintained angle can lead to a host of problems that significantly diminish a knife’s performance and lifespan.

One of the most common issues arising from incorrect angles is premature dulling. If the angle is too obtuse (too wide), the edge will not be keen enough to cut efficiently, feeling dull even immediately after sharpening. If the angle is too acute (too narrow) for the steel’s hardness or the knife’s intended use, the edge becomes overly delicate and prone to rolling or chipping. A rolled edge means the very apex of the blade has folded over, while chipping involves tiny pieces of the edge breaking off. Both render the knife ineffective and require significant effort to correct.

Consistent, correct angles also ensure even wear of the blade material. When angles are inconsistent, some parts of the edge will be sharper and wear faster, leading to uneven cutting performance and requiring more frequent sharpening to re-establish a uniform edge. This uneven wear can also lead to a thicker “shoulder” behind the edge over time, making it harder to sharpen and reducing its cutting efficiency.

Furthermore, incorrect sharpening techniques can lead to excessive material removal, shortening the knife’s useful life. Japanese knives, with their often very thin blades, are particularly susceptible to this. By maintaining the correct japanese knives angle and using proper technique, you extend the period between major re-profiling efforts, preserving the knife’s original geometry and value.

In essence, neglecting the proper angle is akin to driving a car with misaligned wheels; it will still move, but inefficiently, with increased wear and tear. Proper angle maintenance ensures that your investment in a high-quality Japanese knife continues to pay dividends in performance and durability for decades to come. It truly is the foundation of a knife’s longevity.

Troubleshooting Common Mistakes: Uneven Angles and Edge Roll

Even experienced sharpeners can encounter challenges, but recognizing and troubleshooting common mistakes related to the japanese knives angle is crucial for continuous improvement. Two prevalent issues are uneven angles and edge roll, both of which severely impede cutting performance.

Uneven angles often result from inconsistent hand pressure or an unsteady sharpening angle. This manifests as certain sections of the blade being sharper than others, or the edge appearing warped under magnification. To troubleshoot, return to a coarser grit stone (e.g., 1000 grit) to re-establish a consistent bevel. Pay meticulous attention to maintaining a stable angle throughout the stroke, using visual cues (like the slurry on the stone) and the feedback from the blade itself. Practice on a less valuable knife until muscle memory develops. Angle guides or sharpening systems can be invaluable here for achieving initial consistency.

Edge roll, where the very apex of the blade folds over rather than cleanly cutting, is usually caused by an angle that is too acute for the steel’s toughness or the cutting task. It can also occur from excessive pressure during sharpening or improper stropping. To fix an edge roll, you’ll need to slightly increase the sharpening angle, typically by 1-2 degrees, to create a micro-bevel or reinforce the edge. This makes the edge more robust. For very stubborn rolls, a few passes on a coarser stone at a slightly steeper angle might be necessary before progressing to finer grits. Reducing sharpening pressure, particularly during the final passes, also helps prevent future rolls.

Another common mistake is not fully removing the burr. A persistent burr will lead to a seemingly sharp edge that dulls almost immediately upon use. This requires more precise burr removal techniques, such as very light passes on a fine stone or a leather strop, sometimes alternating sides, until the burr completely vanishes. The burr needs to be formed evenly on both sides before being removed cleanly. Patience and meticulous attention to detail are key in all these troubleshooting scenarios. By understanding these common issues and their solutions, one can significantly improve their ability to maintain the perfect japanese knives angle.

When to Adjust: Adapting the Japanese Knives Angle Over Time

The optimal japanese knives angle is not necessarily fixed for the lifetime of the blade; it can and sometimes should be adjusted over time based on several factors. Understanding when and how to adapt the angle is a mark of an advanced sharpener.

One primary reason for adjustment is the evolution of the blade’s profile. As a knife is sharpened repeatedly, material is removed, and the blade naturally thickens slightly behind the edge. This can lead to decreased cutting performance even if the edge angle itself is maintained. In such cases, a technique called “thinning” (uradashi for single bevel, or simply thinning the blade face for double bevel) might be necessary. This involves carefully grinding away material from the sides of the blade above the edge, effectively recreating a thinner profile and allowing for a more acute effective angle without making the very apex too delicate.

Another reason for angle adjustment is a change in the knife’s primary use or the user’s preference. If a knife originally sharpened for delicate slicing is now used more for general prep work involving harder ingredients, a slight increase in the edge angle (e.g., from 12 to 15 degrees per side) can significantly enhance its durability and chip resistance. Conversely, if a knife feels too robust and you desire more slicing precision, a slight reduction in the angle can improve its cutting feel, assuming the steel can handle it.

Damage to the edge, such as significant chips or a severely rolled edge, also necessitates re-profiling, which might involve establishing a new, slightly different japanese knives angle. This is often done on a coarser stone to remove the damaged material quickly and then progressively refined. It is an opportunity to fine-tune the angle for future performance.

Finally, as a sharpener’s skill improves, they might experiment with micro-bevels or convex edges, subtly altering the angle at the very apex to fine-tune sharpness and durability. Adapting the japanese knives angle is part of a continuous learning process, allowing the knife to remain a high-performing tool tailored to the evolving needs and skills of its user.

Beyond the Primary: Micro-bevels and Advanced Japanese Knives Angle Concepts

The Role of the Micro-bevel in Enhancing Sharpness and Durability

While the primary japanese knives angle defines the overall geometry of the edge, the concept of a micro-bevel adds a layer of sophistication, allowing for an optimized balance of sharpness and durability. A micro-bevel is a very small, slightly steeper secondary bevel applied at the very apex of an already sharpened edge.

For example, if a knife has been sharpened to a primary angle of 12 degrees per side, a micro-bevel might be applied at 15 degrees per side, encompassing only the last fraction of a millimeter of the edge. This creates a slightly stronger, more robust tip on the cutting edge without significantly compromising the overall cutting performance provided by the much thinner primary angle.

The advantages of incorporating a micro-bevel are numerous. Firstly, it dramatically enhances edge durability. By reinforcing the most fragile part of the edge, the micro-bevel makes the knife less prone to chipping or rolling during regular use, especially when encountering harder ingredients or during accidental impacts. This means less frequent sharpening and fewer repairs over the knife’s lifespan.

Secondly, a micro-bevel can make sharpening easier and quicker. Instead of needing to sharpen the entire primary bevel every time the knife needs a touch-up, one can simply refresh the micro-bevel. This saves time and removes less steel from the blade, prolonging the knife’s life. It is particularly effective for daily maintenance, where a quick pass on a fine stone or a strop with a slightly steeper angle can bring the edge back to peak performance.

Finally, it can sometimes improve perceived sharpness. A micro-bevel, even if slightly wider, can lead to a more stable apex that cuts more cleanly through tough materials. While it adds a degree of complexity to the sharpening process, mastering the application of a micro-bevel allows for fine-tuning the japanese knives angle to achieve an optimal blend of keenness and resilience, truly pushing the performance boundaries of the blade.

Convex and Concave Grinds: Subtle Nuances of Japanese Blade Angles

Beyond the primary and micro-bevels, the overall grind of the blade, whether convex or concave, adds another dimension to the intricate world of japanese knives angle and performance. These subtle nuances significantly impact how a knife slices and handles.

A convex grind (also known as a hamaguri-ba or clam-shell grind) features a profile where the blade gently curves outwards from the spine towards the edge, rather than being flat. This creates a thicker, stronger edge behind the apex while still allowing for a very acute cutting angle at the very edge.

The convex shape provides several benefits: it reduces friction as it passes through food, preventing sticking, and it makes the edge incredibly robust and resilient to chipping, even at very fine angles. Many traditional Japanese knives, particularly those for heavy-duty tasks like Debas or Axes, incorporate a convex grind due to its superior strength and food release properties. Sharpening a truly convex edge requires advanced freehand techniques or specialized sharpening systems to maintain its specific curvature.

A concave grind (or hollow grind) is less common in Japanese kitchen knives, but elements of it are found in the ‘ura’ side of traditional single-bevel knives. The ura side is often hollow-ground to reduce friction and allow the primary bevel to cut more efficiently while also facilitating the burr removal process during sharpening. In Western knives, a full hollow grind creates a very thin blade towards the edge, making it incredibly sharp but potentially more fragile. While not a primary sharpening angle in itself, the concave geometry of the ura greatly influences the effectiveness of the acute japanese knives angle on the primary bevel, ensuring less drag and cleaner separation of food.

These specialized grinds showcase the meticulous attention to detail in Japanese knife design, where the entire blade geometry works in harmony to achieve a specific cutting performance. Understanding these grind variations is crucial for proper maintenance and appreciation of the complex interplay between the blade’s profile and its ultimate cutting edge.

Re-profiling and Thinning: Advanced Techniques for Angle Correction

Over time, even with careful maintenance, the geometry of a Japanese knife can subtly change. Repeated sharpening, especially if done inconsistently, can lead to the edge becoming thicker behind the apex, making the knife feel duller even when razor-sharp at the very edge. This phenomenon is known as “shouldering” or “over-sharpening” the edge. In such cases, advanced techniques like re-profiling and thinning become necessary to restore the knife’s original cutting performance and optimal japanese knives angle.

Re-profiling involves completely reshaping the primary bevel of the knife to establish a new, more optimal angle or to remove significant damage like large chips. This usually requires starting with very coarse grit stones (e.g., 120-400 grit) to remove substantial amounts of steel. It’s a precise and time-consuming process that requires a deep understanding of blade geometry to avoid damaging the knife. The goal is to set a new foundation for the edge that is perfectly symmetrical (for double-bevel) or correctly oriented (for single-bevel).

Thinning, also known as ‘kasumi’ finishing or ‘uradashi’ for single bevels, addresses the issue of the blade thickening behind the edge. This technique involves grinding away material from the entire blade face, above the primary bevel, to reduce the overall thickness of the blade. For double-bevel knives, this means grinding the ‘cheeks’ of the blade to create a thinner cross-section. For single-bevel knives, it involves meticulously working on the ‘shinogi’ line and the primary bevel to restore the delicate convex or flat grind that allows the knife to glide through food with minimal resistance.

Thinning directly impacts the effective japanese knives angle. By reducing the material behind the edge, even if the apex angle remains the same, the knife cuts more efficiently because there’s less wedge effect. This process can significantly rejuvenate an old or overworked knife, restoring its “out-of-the-box” cutting feel. Both re-profiling and thinning are advanced skills that require significant practice, patience, and a keen eye for detail. They are crucial for the long-term health and performance of high-quality Japanese knives, ensuring they continue to perform optimally for decades.

The Art and Science of the Perfect Japanese Knives Angle

Summarizing the Path to Unparalleled Edge Performance

The journey to mastering the perfect japanese knives angle is a blend of art and science, demanding precision, patience, and a deep appreciation for metallurgy and geometry. We’ve explored how the unique philosophy of Japanese knife making, steeped in centuries of sword-craft, prioritizes acute angles for unparalleled sharpness and specialized cutting tasks.

From the distinct characteristics of single-bevel and double-bevel designs to the subtle influences of steel hardness, blade profile, and the knife’s intended use, every element contributes to the optimal angle. We’ve seen that the choice of angle is a deliberate decision, balancing razor-sharpness with necessary durability.

The path to maintaining these exquisite edges involves traditional freehand whetstone sharpening, which fosters an intuitive understanding of the blade, complemented by modern angle guides and measurement tools for consistency and precision. Recognizing and troubleshooting common issues like uneven angles and edge roll are vital skills for continuous improvement.

Furthermore, advanced concepts such as micro-bevels enhance edge longevity and ease of maintenance, while understanding convex and concave grinds reveals deeper layers of blade geometry. Techniques like re-profiling and thinning ensure the knife’s long-term performance, addressing the natural thickening of the blade over years of sharpening.

Ultimately, achieving unparalleled edge performance from your Japanese knives is an ongoing commitment. It’s about respecting the craftsmanship embedded in each blade and dedicating the time to understand and maintain its critical japanese knives angle.

A Lifelong Journey: The Continuous Pursuit of Japanese Knives Angle Mastery

Mastering the japanese knives angle is not a destination but a lifelong journey of continuous learning and refinement. Each knife, each steel, and each sharpening session presents unique challenges and opportunities for growth. It requires a dedication that extends beyond simply making a knife sharp; it’s about understanding the soul of the blade and coaxing out its peak performance.

As you gain experience, you’ll develop an intuitive feel for the blade, an understanding of how different steels behave on the stone, and the subtle variations in angle that yield the best results for specific tasks. You’ll learn to listen to the knife, feeling the feedback from the burr and observing the slurry on the stone, turning the act of sharpening into a meditative and rewarding practice.

The pursuit of angle mastery also opens up a deeper appreciation for the artistry and engineering behind Japanese knives. It transforms you from a mere user into a custodian of these magnificent tools, capable of restoring and maintaining their legendary sharpness. This continuous engagement with your knives not only enhances their performance but also enriches your culinary experience, making every cut a testament to precision and care.

Embrace the challenge, enjoy the process, and know that every stroke on the whetstone brings you closer to the true essence of japanese knives angle mastery. Your knives, and your cooking, will thank you for it. 🔥🎯✅💡

Explore more fascinating insights and guides on Japanese knives:

- Knife Care and Maintenance

- Understanding Knife Materials

- Choosing the Right Japanese Knife

- Japanese Kitchen Knife Sets

- Essential Sharpening Accessories

Visit us at https://japaneseknivesworld.com/ for all your Japanese knife needs and knowledge!